My .gitconfig file dissected

This is my .gitconfig1. Many are like it, but this one is mine.

It’s not long. It’s not complicated. But it configures my workflow’s most important tool. I will dissect the file to better understand how git works and help the reader improve their own workflow.

[user]

name = Kiran Rao

email = hi@kiranrao.ca

signingkey = AAAAABBBBBB

[gpg]

program = gpg

[commit]

gpgsign = true

[alias]

co = checkout

ci = commit

st = status

br = branch

di = diff

fp = fetch --prune

rb = rebase

hist = log --graph --abbrev-commit --decorate --date=short \

--format=format:'%C(bold cyan)%h%C(reset) %C(bold green)(%ar)%C(reset) %C(white)%s%C(reset) %C(dim white)%an%C(reset) %C(bold yellow)%d%C(reset)' \

--branches --remotes --tags

git = !exec git

gti = !exec git

[push]

autoSetupRemote = true

default = current

What is git config?

A .gitconfig is a file that configures git. But it’s not the only one.

There are three files that tell git how to operate.

Running git config --add will append one of these files.

In order from lowest to highest priority:

- System:

/etc/gitconfig. Applies to all users on a system. It is configured with the--systemargument. - User:

~/.gitconfig: Applies to all repositories of a user. It is configured with the--globalargument. - Repo:

.git/config: Applies to a single repository. It is configured with no arguments.

This article dissects my user git config. However, the configurations apply at all levels.

User section

The user section is my name and email.

[user]

name = Kiran Rao

email = hi@kiranrao.ca

But where is it actually used? The user’s name and email get included to every commit and tag. This is clearly visible when running git log:

commit ce97934132deb2b322c54de68ccbc1d402ca18e4 (HEAD -> git-config)

Author: Kiran Rao <hi@kiranrao.ca>

Date: Fri Jun 14 20:31:03 2024 -0400

WIP: User section

The user section yields a useful insight: It’s easy to change my name and email per repo. Separate work and personal, or multiple clients is an example use case.

It leads to another insight: Nothing stops me from changing my user name and email to anything. Nothing stops anyone from changing their name and email to mine. Luckily we have GPG to mitigate that.

GPG key signing

GPG is a public-key cryptography system used to sign commits. It ensures commits published were made by me (someone with my private key or access to my GitHub account).

signingkey = AAAAABBBBBB

[gpg]

program = gpg

[commit]

gpgsign = true

The configuration instructs git:

signingkey = AAAAABBBBBB: The signing key to useprogram = gpg: The program used to signgpgsign = true: To automatically attach a signature to every commit

The signature is visible using git log --show-signature:

commit da7c2d3863581f00d489c0852a91bc15ba98eae0 (HEAD -> git-config)

gpg: Signature made Fri Jun 14 21:00:11 2024 EDT

gpg: using EDDSA key BA8B30A6D0E47B0B447FD15DC0B595B4F1573243

gpg: Good signature from "Tigger 2024-06-11 <hi@kiranrao.ca>" [ultimate]

Author: Kiran Rao <hi@kiranrao.ca>

Date: Fri Jun 14 21:00:11 2024 -0400

Start GPG

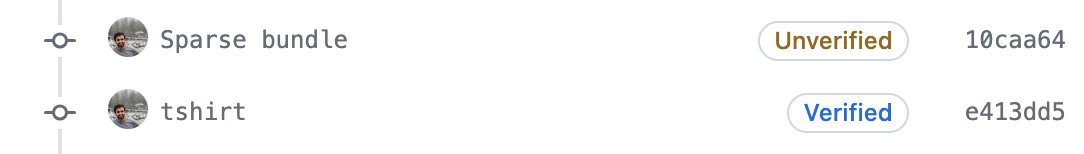

Commits now appear “verified” in GitHub, GitLab, and other git platforms.

I cannot go in-depth into how GPG signing works. How (and why) to sign Git commits is an excellent article on the topic. For a practical guide on setting up GPG for a GitHub account, Generating a new GPG key and Adding a GPG key to your GitHub account

Alias common actions

I use Git aliases for common commands to save keystrokes.

[alias]

co = checkout

ci = commit

st = status

br = branch

di = diff

fp = fetch --prune

rb = rebase

While each alias only saves a few moments, it quickly adds up.

Pretty commit history

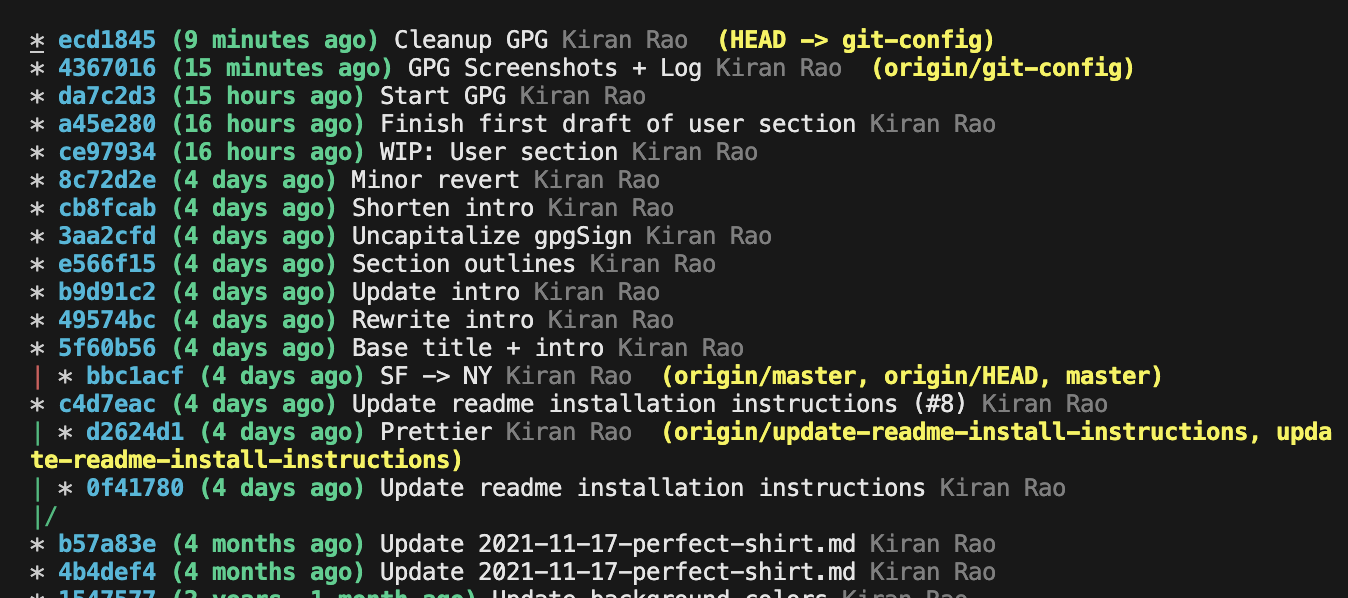

I’ve aliased commands too long to write comfortably. git hist uses git log to show a project’s commit graph.

hist = log --graph --abbrev-commit --decorate --date=short \

--branches --remotes --tags \

--format=format:'%C(bold cyan)%h%C(reset) %C(bold green)(%ar)%C(reset) %C(white)%s%C(reset) %C(dim white)%an%C(reset) %C(bold yellow)%d%C(reset)' \

Normal git log shows a linear history. It can be configured to show way more.

--graph: Graphs*--*--*beside each commit, showing how they relate to each other.--abbrev-commit: Shortens commit length--decorate: Short for--derocate:short--date=short: Shortens date--branches: Shows all branches, not just the curent branch.--remotes: Shows the local copy of all remote branches.--tags: Shows tags--format=format:'...'Applies a fancy format that I copied from somewhere years ago.--onelineis equivalent (but doesn’t look as good)

Put together, git hist shows my project’s commit graph:

git hist was especially useful as a new git user.

I could quickly see the project’s commit graph after each merge, rebase, or cherry-pick.

git hist is also indispensable when debugging failed operations.

I now know the exact state of each branch in the repo.

Time-saving aliases

I’ve mindlessly typed git git status far too many times.

One approach is to punish the behavior.

“I should train myself to be better at typing so that I don’t make this mistake”.

I disagree. Avoiding git git doesn’t improve the structure of my thinking. Instead, I smooth over the papercut.

git = !exec git

gti = !exec git

!exec executes eveything after as a terminal command.

In this case running git again with all arguments. git git status becomes git status. It’s also recursive!

Auto setup remote

If I create and push a branch, I’ll often run into the error:

fatal: The current branch new-branch has no upstream branch.

To push the current branch and set the remote as upstream, use

git push --set-upstream origin new-branch

This is dumb. If a local branch doesn’t have an upstream branch, I always want to create one.

[push]

autoSetupRemote = true

default = current

Setting autoSetupRemote = true and default = current automatically creates an upstream branch without having to use special args.

I’ll never encounter this error again!

Conclusion

Dissecting my simple .gitconfig file reveals a lot. Hopefully you now have a deeper understanding of git and how to use it. I also hope .gitconfig has become less intimidating. Go modify your own!2

-

This is not actually my .gitignore. It’s pretty close. I’ve rearranged and ommited a few pieces for privacy and clarity. ↩

-

This is not legal advice. I’m not responsible, nor will I be tech support if you misconfigure git. But if you find something cool, let me know! ↩